Our Verdict

For better and for worse, Dragon’s Dogma 2 is a faithful reimagining of Hideaki Itsuno’s flawed yet ambitious action-RPG. Those who rise to the challenge of meeting it on its own terms are suitably rewarded, but a deluge of trash mobs, restrictive fast travel, and endemic hardware issues will be a dealbreaker for many.

Among countless soulslikes and nondescript action-RPGs, Dragon’s Dogma 2 stands as a game from another time. It’s de rigueur to point to the latest open-world game and draw parallels to Elden Ring or Breath of the Wild, but Capcom’s sequel is closer to how Neverwinter Nights exists in my childhood memories, calcified in rose-tinted nostalgia. For many, that niche was likely filled by Baldur’s Gate 3 last year, but there’s something to be said for Dragon’s Dogma’s drab medieval fantasy that echoes a bygone era. Dragon’s Dogma 2 is closer to a reimagining than it is a sequel, the full realization of all that game director Hideaki Itsuno was trying to achieve with Dragon’s Dogma back in 2012. It’s a sentiment that’s echoed by its main menu, curiously bereft of a number. Instead, Capcom delivers a world that’s both different and yet very much the same.

While the first Dragon’s Dogma establishes the bizarre rules that govern the social fabric of its universe (a dragon, a stolen heart, and a very cool scar), its sequel is more preoccupied with how those rules can be bent, if not broken. To paraphrase Monty Python, strange dragons appearing out of nowhere and stealing hearts is no basis for a system of government, and so Dragon’s Dogma 2 kicks off with a good old-fashioned royal plot, complete with a conniving queen regent and a pretender king. It’s a far more approachable story pitch than the seaside open-heart surgery of the first game. Instead, Dragon’s Dogma 2 leans into its pseudo-medievalism, as dukes and duchies are elevated to kings and kingdoms.

It certainly helps that Dragon’s Dogma was as much ahead of its time as it is of its time. Some may consider the pawn system to be its most defining mechanic, but this goes hand in hand with the vocation system. The ability to effortlessly switch between classes might well be my favorite aspect of the series, allowing for extensive build customization across a range of playstyles, especially once hybrid vocations are on the table. However, Dragon’s Dogma 2 encourages me to switch things up to an unprecedented degree. A chance encounter with a curious elf archer prompts me to switch to the same vocation so that I might give him a demonstration of how to wield a human-made bow.

This marriage between quest and combat design invites me to step out of my comfort zone, but after a colorful career as a Mystic Knight back in Dragon’s Dogma: Dark Arisen, I went into the sequel a touch bereft in its absence. What could ever replace the awesome elemental power of my magick shield? The answer to that question is the Mystic Spearhand, a polearm-twirling hybrid vocation that’s basically the Jedi Knight of this universe. I levitate rocks to hurl them at enemies, send goblins hurtling fifty feet into the air, and drain their life force to replenish my stamina. The power fantasy is incredible– right up until I encounter an enemy capable of flight, and then I’m almost entirely reliant on my pawns to bring them down. Party composition remains as accommodating in Dragon’s Dogma as it was back in Dark Arisen, allowing me to experiment with class combinations at my leisure. Naturally, there are some unspoken rules: foregoing a healer demands your party rely on curatives to survive tough battles, and a blend of vocations allows you to cover all bases. However, once you add a mage and sorcerer to the mix, the visual clarity of fights can quickly degrade into a Pollockian mish-mash of explosions, elemental magic, and flailing bodies. Can I see what’s going on? Not really, but it does feel very cool.

I’ll admit, I was skeptical of Capcom’s claims that pawns would have more of a personality in Dragon’s Dogma 2. I never really had much of an attachment to any of these AI-controlled allies in Dark Arisen, but the combination of inclinations, specializations, and an extensive character creator ensures that they’re visually distinct and genuinely helpful. My main pawn is a solemn, soft-spoken beastren, a solid wall of fur, muscle, and plate mail that I fondly refer to as ‘Cat Dad’. He’s also a logistician, which means he takes care of the arduous inventory management that bogged me down back in Dark Arisen. In short, I love him – which is a relief, since I’m pretty much stuck with him. Hired pawns still come and go, but they don’t feel quite as transient as they did back in Dark Arisen, in part due to how they interact with one another. When two pawns commented on how well they worked together as a team, I felt a pang of guilt knowing that one of them was now too low-level to support my party and would have to go. Conversely, I sent one pawn packing after their rambunctious personality clashed with Cat Dad.

That said, travel with any pawn for long enough and their barks are liable to become repetitive, especially if you’re not in the habit of following their observations. “This ladder can take us to new heights!” became an exhausting refrain every time I stepped foot in Vernworth, to the extent that I eventually climbed said ladder just to shut them up. Pawns also tend to react to situations in tandem, resulting in sequential barks that all express the same sentiment. This wild oscillation between affection and annoyance towards pawns won’t be new to any long-time fans of the series, and it’s easy to forgive these irritations when you’re high-fiving your pawn on top of a downed ogre.

Outside of monster-slaying, the world of Dragon’s Dogma 2 strikes a fine balance between existing for itself just as much as its player. NPCs won’t complain if you loot a chest or take a coin purse lying around their homes, but they’re not at your every beck and call either. As in Dragon’s Dogma: Dark Arisen before it, the world moves right along with you. Many NPCs have a daily schedule that demands you to meet them at specific locations at certain times of the day, and you may even need to wait on them before you can see a quest to fruition. Equally, if you pledge to help someone and then consign their request to the bottom of your quest log, you might find they eventually attempt to undertake it themselves – and meet a grisly end in the process. Questlines can be broken if you neglect to treat them with the care that they deserve, and some interactions don’t even manifest as a quest at all. In that respect, Dragon’s Dogma 2 is an improvisational sandbox game, where a ‘yes, and…’ approach is rewarded with a far richer experience than keeping a single-minded focus on the main story.

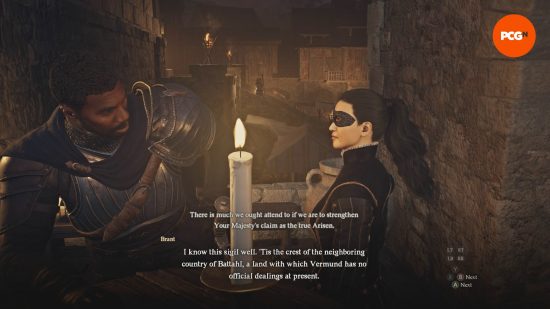

This emergent quest design applies to the world at large, in a bid for total immersion. There are no floating icons to be found here; instead, mercantile NPCs are marked by the signs advertising their wares, and quest givers typically bump into you at random to strike up a conversation. It can occasionally become overwhelming – try making it through your first trip to Bacbattahl unimpeded on your way to the palace – but it feels far more organic than my usual impulse to stop by anyone with an exclamation mark above their head and create a shopping list of quests to complete simultaneously. There’s also a connective tissue running through certain quests that make for some pleasant surprises. A reward for completing one quest might be just what you need to complete another.

Capcom also dispenses with the notice boards full of awkward escort missions and monster-culling errands in favor of more high-value quests that deliver meaningful experiences. Newcomers might be surprised to discover that a quest log in Dragon’s Dogma 2 is just that: a log. It doesn’t offer any particular clues beyond what you learn from NPCs and flavor text, but this also leaves room for alternate solutions. I opt for an Agent 47-style infiltration of the queen regent’s chambers by throwing on a suit of armor and pretending to be one of the palace guards, though I’m still not entirely sure whether or not my disguise made a difference. I relish this ambiguity, but it also creates a space for frustration when a quest devolves into moon logic or a sudden dead end. In these moments, I’m grateful for the Oracle, a new NPC that allows me to pay a pittance of gold in exchange for a riddle indicating the next stop on my journey.

The dense forests and pastoral settlements of Vermund are analogous to Gransys, but the new region of Battahl represents a whole new frontier: a desert replete with red rock canyons, ancient ruins, and perhaps most importantly, the Beastren. The Elder Scrolls has already endeared me to feline races in medieval fantasy thanks to the nomadic Khajit, so it should come as little surprise that the Beastren are a natural fit. No matter the region, the open world’s topography follows the same principles as you expect from Dragon’s Dogma: a thick, serpentine road winds its way around an oddly misshapen map, branching off into minor paths that invite you into the undergrowth to discover sunken caves, forgotten riftstones, or even just a simple treasure chest.

However, the influence of landmark open-world games draws stark attention to the limitations of traversal. The ability to free-climb colossal enemies but not the wider environment is barely worth a second thought in Dark Arisen, but in the wake of Breath of the Wild, it’s frustrating to fall down a hill during a skirmish with an ogre and be forced to take the long way back up, leaving your pawns to issue the killing blow. Equally, the decision to bring back the Brine rather than implement a swimming mechanic can often leave you staring wistfully at the other side of a riverbank, with no way to cross.

It’s not just the terrain that poses a challenge; the enemy density in the open world is oppressively high. From the forest trails of Vermund to the canyon paths of Battahl, I am constantly inundated by wolves, goblins, and harpies. These combat encounters occur in quick succession, allowing me scant seconds to breathe, and occasionally spill into each other in a menagerie of teeth and claws. While these basic encounters present the perfect opportunity to get to grips with a new vocation or optimize skill rotations, their sheer frequency quickly becomes a nuisance when I’ve got my heart set on a destination. They also leave me with the overall impression that Capcom is afraid that I’ll grow bored if I have a moment to myself, which couldn’t be further from the truth; sometimes, I just want to take in the beautiful scenery and share a quiet moment with my pawns. Presumably, this is Capcom’s answer to the common complaint about on-foot exploration in Dragon’s Dogma: Dark Arisen, but I am not exaggerating when I say at one point I was fending off two cyclopes, a griffin, a pack of wolves, and a gaggle of hobgoblins simultaneously. Needless to say, I didn’t survive that encounter.

It’s in times like these where victory is just impossible, no matter how many curatives you have stocked. Thankfully, the autosave is very attentive, depositing me only a short walk away from where I fell so I can take another crack at the encounter or choose to go elsewhere. Dragon’s Dogma fans will recall the difficulty spikes endemic to certain areas in Dark Arisen, but these pain points are less obvious in the sequel. This is in part thanks to the sheer size of Dragon’s Dogma 2’s map, which is large enough that there are plenty of other places to go if you find yourself in a bind. This brings me to the fast travel system, which is deliberately restrictive to encourage exploration on foot. Oxcarts can only take you so far, and Ferrystones are few and far between – and even then, they can only teleport you to Riftstones you’ve discovered along the way.

There’s no getting around it: this will be make-or-break for most players. It’s by far the most divisive aspect of the series, to the extent that Dark Arisen bestowed us with an Eternal Ferrystone to ease our woes. As someone who dislikes the overreliance on fast travel in open-world games, I find that this grounded approach to exploration begets an appreciation for its scale; we often hear about the size of in-game maps, but rarely are we forced to feel it. Every time I set out from Vernworth or Bacbattahl with my Pawns, weighed down with supplies for the road, I feel like Frodo striking out from Rivendell. Admittedly, it feels far less grandiose when I’m stuck in a desolate fishing village on some desolate corner of the map, pining for home – but then again, it also felt like that for Frodo.

Dragon’s Dogma 2 may be leaps and bounds ahead of Dark Arisen on a technical level, but it’s far from a hyper-polished experience. NPCs won’t always turn to look at you while speaking, while pawns will occasionally run into walls and make no attempt to correct their pathing. That said, one player’s jank is another player’s treasure, and I don’t think I’d want a version of Dragon’s Dogma that’s missing the spontaneous comedy of a pawn following an enemy over a cliff like a bloodthirsty lemming. These are all forgivable, the little flaws that fans will undoubtedly see as part of its charm. Unfortunately, I can’t in good conscience recommend anyone with a mid-to-low-budget rig buy Dragon’s Dogma 2 until Capcom fixes its endemic hardware issues.

The inconsistent framerate is the biggest offender. While the drops are less severe in the open world, I spend most of my time in major cities staving off a headache as my Arisen is reduced to a stop-motion picture. The only member of the PCGamesN team who didn’t experience any framerate issues is running it on an Nvidia RTX 4090 – something that the vast majority of players don’t own, and indeed, shouldn’t need to own to run Dragon’s Dogma 2. However, not even a top-end graphics card will save you from the random freezes, which often leave me fretting over the corruption of my single save file.

I’ve also spent a frankly exhausting amount of time in the system settings menu in an attempt to fix visual textures smeared with Vaseline, polygonal shadows, and miasmic reflections with varying degrees of success. I can only put this down to poor optimization, and while I’m sure these issues will be massaged out in post-launch patches, it’s such a very great shame. I’d have welcomed a delay to experience the buttery-smooth framerate and striking visuals I’ve seen in gameplay trailers and previews. Doubtless, some players will experience no issues (such is the vicissitude of hardware) but this is a surprising dark spot on the otherwise glowing reputation of the RE Engine and Capcom’s PC ports in general.

Ultimately, Dragon’s Dogma 2 is a bizarre game full of bizarre choices. Take the campfire cutscene: a live-action, slow pan over a sizzling slab of meat. It’s so incidental, but the singular choice to harness the latest technology to create what amounts to a modern-day version of an FMV cutscene from the early nineties is emblematic of Dragon’s Dogma as a whole. I was worried that Capcom would capitulate to expectations of what an open-world RPG releasing in 2024 should be, and in doing so, minimize the very same idiosyncrasies that made me fall in love with the series in the first place. The on-foot traversal, hands-off quest design, and dialogue straight out of a Shakespeare in the Park production won’t be to everyone’s taste, but it is definitely to mine.

Amid the burgeoning homogeneity of big-budget game design, I have to respect Itsuno’s unwavering commitment to his vision for this series. However, this same ambition to take a second (technically third) swing at crafting a definitive version of Dragon’s Dogma means that it can never stray from the very same systems and mechanics that made the first as divisive as it is. Setting all that aside, it is impossible, and frankly irresponsible, to ignore the hardware problems that have plagued PCGamesN’s collective experience with the PC version. I’m more than ready for Dragon’s Dogma 2 to steal my heart; it just has to do it at a stable framerate first.