Our Verdict

Successfully modernises the medieval strategy series, preserving much of what's good and adding some interesting new ideas. While it still needs to iron out a few details, it's a worthy successor to the series' august crown.

Arriving as it does on the eve of what may be a succession crisis in the United States – that grand experiment in Enlightenment ideas of popular sovereignty – it’s tempting to think of Crusader Kings III as a kind of divine omen. Paradox’s latest incarnation of its medieval dynasty simulator is not only strangely portentous, it’s also the most accessible the studio’s grand strategy games have ever been. Thanks to a near total rework of its interface, an enhanced new build of the underlying Clausewitz engine, and a generous new system for keeping players informed, Crusader Kings III is the new gold standard for the genre.

Over the past several years, the idea of keeping politics out of videogames has gained a certain amount of traction, and Crusader Kings III continues in the tradition of vividly demonstrating the absurdity of that notion. The American political scientist Harold Lasswell wrote that politics is the process of determining “who gets what, when, and how,” and that’s a decent summation of what Crusader Kings is about. Every decision you make is inherently political, and the politics of the middle ages is a swirling vortex of relationships, tradition, violence, and wealth in which you immediately find yourself fighting for dominance – or in many cases, mere survival.

Veterans of Crusader Kings II will be immediately familiar with the setup. You choose a start date, then a ruler alive during that time, and then set off in a medieval sandbox to fulfil whatever goals you’ve decided upon – unify a shattered kingdom, restore a faith, or just fight for all the glory you can in order to secure your legacy and see that your family’s name lives on through the ages.

The most difficult thing about any Paradox game, I’ve found, is understanding what it is – and that’s particularly true of the Crusader Kings games. They look big and intimidating, and starting off it can be hard to set aside preconceived notions about what to expect from a strategy game. Crusader Kings III is a game about people, but the majority of what you’ll be doing as you play is staring at a map. This is a role-playing game as much as it’s about strategy, and you’ll be making decisions about how to proceed with character development, murder plots, and familial squabbles while you’re commanding your armies to lay siege to an enemy fortress.

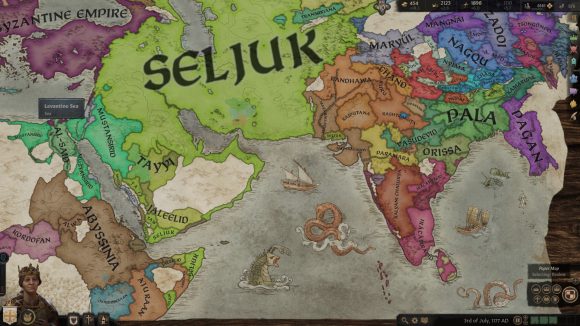

While Crusader Kings III lacks the more baroque (and frequently humorous) intrigue schemes and story beats added to its predecessor in its later expansions, seasoned players can rest easy knowing this isn’t starting back at zero. At launch, Crusader Kings III includes a much larger map that stretches from Iceland in the northwest corner to include all of Europe, the northern half of Africa, and the Indian subcontinent.

What a map it is, too. The revitalised Clausewitz Engine renders your view of the world in a scaling parchment map that populates with hills, forests, deserts, mountains, and oceans as you zoom in. It’s beautiful to behold, and each view is rendered in a colourful, hand-drawn style when you’ve pulled back to take it all in. Crusader Kings III feels snappier, faster, and easier to navigate thanks to the refreshed UI, which has discarded the busy stonework-and-stained-glass aesthetic of Crusader Kings II in favour of a simpler, less distracting system that uses subtle colour coding to help keep you focused on what matters.

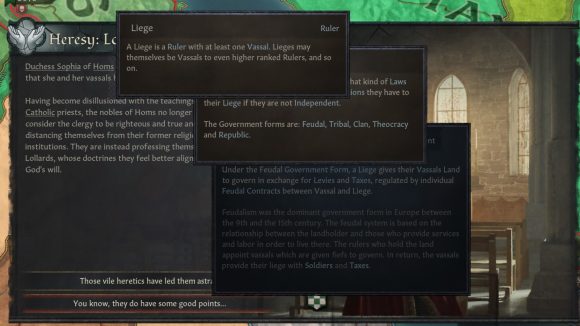

New players will find it much easier to get their bearings in Crusader Kings III. Almost every element of the game has an associated tooltip, and these can be frozen in place by hovering over them briefly (the length of time is even adjustable). Once that’s done, you can mouse over highlighted text within the tooltip to bring up another tooltip. This can be done indefinitely, allowing you to follow game elements from their most specific and arcane back to more generalised concepts. It’s devilishly helpful, and it prevents new players from feeling overwhelmed with information. Further to that, there’s a brand new tutorial, this one set on the community-christened ‘Newbie Island’ of Ireland, which does a much improved job of introducing its core concepts.

That’s not to say that Crusader Kings III solves all the organisation problems that characterised Crusader Kings II. Being a monarch is tough, and European rulers have limits on the number of titles they can personally hold before their vassals start grumbling behind their backs. This means you’re often trying to divest yourself of duchies and counties, and sorting out who has de jure claims to titles you hold should be simple enough to handle in a single dialog box. There’s no straightforward way to cross reference your held titles with the claims of your vassals, even though this is the business you’ll find yourself engaged in for a good chunk of any playthrough.

Four times the fun: The best 4X games on PC

There are other small annoyances as well, thanks largely to the fact that there’s so much going on at once. Key decisions will pop up as you’re tracking the progress of a siege, for example, and crucial text will be obscured by overlapping information boxes. Right clicking to dismiss announcement scrolls at the top of the screen has routinely resulted in mistaken commands to a selected army, who I’ve unintentionally ordered to march to whatever county was directly behind the notification I was trying to hide.

It pains me to point out these flaws because Crusader Kings III is brilliant. It’s a game that makes me happy to own a beard, because it’s the perfect thing for some good beard-stroking. You can set your own goals when you begin, but in general what you’ll be doing is managing the accretion of those titles to your family’s name. The ‘game’ part of Crusader Kings III is, as ever, the wobbly balancing act of picking which titles to hold onto and which to hand out in order to placate the jealous vassals, and doing this in a constantly shifting world of competing houses, cultures, and personalities. You’ll also be worried about defending your realm against forces eager to chip off a juicy county, or perhaps absorb you entirely. It’s a legalistic game in which a certain amount of rule-breaking is accounted for in the rulebook. A perfect example: you can’t go to war without an officially recognized casus belli, but you can always send your cleric off to simply make one up.

Of course, your pretext for wars and the ways they’re resolved are largely dependent upon your chosen culture. Crusader Kings III offers two start dates, 867 and 1066, and in both you’re given hundreds of rulers to pick from. The raider tribes of the north seas have their own customs for succession, and the sheiks of Mesopotamia have others still. You aren’t restricted to medieval European Catholicism this time around – you can play as pagan, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain rulers in addition to adherents of the ‘default’ pre-Reformation Christian sects, and the Great Khans will storm out of the east to conquer much of the known world beginning around 1200. There’s still plenty of room to grow into, however: the ragged eastern edge of the map is ripe for the addition of feudal China, perhaps beginning with the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period beginning around 910 AD.

One of my favourite new additions in Crusader Kings III is the secrets and hooks system. Paradox revealed this ahead of release, and I worried that it looked too fussy to actually be useful. The opposite is the case: hooks represent favours that can be called in at key moments, and you can earn them by releasing captives, discovering secrets (nobody wants their adultery revealed to the rest of Catholic Europe), and using blackmail. You can look at the hooks you hold in a tab in the intrigue panel, and it’s like having a little black book of dirt to use at opportune moments.

If you’ve chosen certain lifestyle perks during your ruler’s development, you can even use these to demand shakedown money, but they’re much more satisfying to pull out when making deals over marriage proposals or feudal contracts. Sure, you might not want to increase your levy contribution, you might tell one indiscreet lord, but there was that one time, at the feast, when you and… right, I thought so. Your vassal won’t be thrilled about it, but they won’t make much noise, either – having a favour hook allows you to ‘modify’ feudal contracts without publicly marking yourself out as a tyrant.

Plate spinning: The best management games on PC

You’ve got to be cut from the right kind of cloth to be a truly devious ruler, however. The new stress system allows you to see how certain decisions will add or relieve stress, and your character’s attributes impact this calculation. Just characters will have a hard time with overly punitive decisions, while lazy characters won’t want to do anything that involves too much walking around. Hitting certain stress thresholds will lead to your character becoming overwhelmed, and too much stress for too long can be fatal. It’s a system that’s deeper than it appears at first, and rewards players for digging into the idea of truly role playing as the character they’ve nurtured and developed.

Something ought to be said here about the new 3D character models as well. While they’re easy enough to dismiss out of hand as simple fluff, it’s difficult to overstate the impact they have on the experience. Rather than the static portraits of old, these rendered models change dynamically over time, and their battle scars and syphilis lesions add meaningfully to their impact on the game. More than once I’ve handed extra titles out or been quicker to ransom vassals who look particularly pathetic, especially when it’s been the result of wars I’ve waged to satisfy my own overweening greed.

Combat’s had a bit of a rework as well, but still feels somewhat flat. You have more options now in terms of force composition thanks to the new men-at-arms system that allows you to pay regiments of professional soldiers to accompany your levies in times of war. Effectively this means adding quality and specialisation to your big blob of soldiers – with the right advancements unlocked, you can field units of trebuchets and armoured horsemen to accompany your untrained peasant rabble, and the impact of these can be impressive: a smaller group of better-trained professional soldiers can take on poorer-quality troops in larger numbers, particularly if you can choose an advantageous place to fight.

That said, wars still too often devolve into chasing smaller but still siege-capable armies around contested territory, and in situations where you have multiple AI allies (notably crusades), trying to coordinate your movements is nigh impossible. Gladly, there’s no longer any need to manage transport ships now (that’s all been abstracted to an ’embark cost’ in gold when you set sail), but more fundamental changes to combat would have been welcome. Love them or hate them, the big changes that came to combat in Hearts of Iron IV show that more is possible, and Crusader Kings III doesn’t take any bold steps on that front.

In the end, though, that’s okay. Crusader Kings III is a game about the politics of the divinely anointed, in a time before rulers had much use for concepts like ‘The People’ as a political entity. As ruler, your will and the will of the nation are synonymous, because there’s no nation outside the title you and your family hold. To the kings and queens, the chieftains and sultans of Crusader Kings, the people who live in their holdings are merely another natural resource, and the notion that they might have a popular will that should be accounted for won’t show up in Europe for another couple of centuries. They’re invisible until they organise a peasants’ revolt, at which point you must crush them with the overwhelming might of your throne. You’re concerned with the broad strokes of war, not with the grubby business of fighting – that’s what your levies and commanders are for.

It might be helpful to think of Crusader Kings III as a piece of editing software that uses a historical vocabulary of events, people, and places to build elaborate stories. Crusader Kings III is the upgraded, modern version of this software. It doesn’t teach history, but it gives you history’s driving principles to illuminate the politics of the feudal world, and I feel I’ve learned more effectively from it than I did in any classroom. It arrives in a world where some of the most powerful nations are being rent apart before our eyes by the politics of personal power and ambition, and thus it also serves well as a rather grim meditation on what happens when the distinction between the nation and the ruler ceases to be meaningful.

For new players, Crusader Kings III offers the smoothest introduction to Paradox’s ambitious grand strategy approach to date, and for seasoned vets, the improvements and additions make the jump from Crusader Kings II worth the sacrifice of some favourite expansions. Crusader Kings II proved to be a very important game for Paradox and introduced grand strategy to a massive new audience, arguably setting the company on the path it has been on ever since. It seems unlikely that Crusader Kings III will have the same kind of impact, but it is inarguably the better version of the game. I’m excited to see where it goes from here.